Editor’s note: This 3-part blog series on war crime, with special attention to the representation of Nazis in prime-time American TV, was written before the events in August in Charlottesville, VA and are not reflective or responsive of contemporary events involving terror white supremacy, neo-Naziism groups, etc. As this 3-part blog series focuses on the fictional representations of war criminals in American television, thoughtful discussions are absolutely welcome on topic. I understand that these topics have become more relevant in current politics; however let me be clear about where I stand on this issue. I absolutely denounce racism and bigotry of all kinds, and consider this a safe place for open and thoughtful discussion. Any comments encouraging racism, white supremacy, anti-semitism, anti-social behaviour and violence will not be tolerated; comments will be reported and removed.

This blog entry is part two of three: the purpose of this series is to explore how perpertrators of war crimes are treated after the war in various points of genre television. Part one of this blog explores an episode of The Twilight Zone (referred to in this blog as TZ) episode ‘Deaths-Head Revisited’, and contextualises the attitudes of Rod Serling, post-war attitudes in the 1960s, as well as some historical background of the programme. If you missed Part one and wish to read it now, please click here. Below, this second blog will focus on the 1981 episode of Magnum, P.I., ‘Never Again… Never Again’. The final entry in this 3-part blog series focuses on a 1993 episode, ‘Duet’, in the science fiction programme Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Each blog will examine how those who committed crimes of war are treated within these television episodes. As always, spoilers are ahead.

‘Never Again… Never Again’ – Magnum, P.I.

Season 1, Episode 7

Aired: 22 January 1981

Story by: Jim Carlson, Terrence McDonnell Teleplay by: Babs Greyhosky

Directed by: Robert Loggia

Magnum, as an hour-long programme (45 minutes without adverts) is afforded more time for a more complex narrative – as well as cast. It is an interesting idea, but unlike ‘DHR’ and ‘Duet’, Magnum is an action-adventure programme. The opening credits show you exactly what to expect: helicopter chases, Hawaiian beaches, guns, Tom Selleck without a shirt, flashbacks to ‘Nam, Navy uniforms, explosions, beautiful bikini-clad women, car chases, Higgins with a cannon, random tomfoolery with his friends Rick and T.C., more fights, more beaches — all done with a flirtatious and knowing wink from Tom Selleck as he smiles at the camera.

As always, some context in this programme and this era is important. DHR in TZ was less than two decades away from the end of WWII – and as such, the appearance of Nazis in TZ made a bit more sense. Even Magnum is a bit incredulous at the idea of fighting Nazis in 1981 Hawaii – and Rick shows more than a little concern, saying ‘Thomas, I don’t know if I’m ready for Nazis!’

Let’s get this out of the way: ‘Never Again… Never Again (NANA)’ is not a great episode – certainly not one of Magnum‘s best (and definitely no ‘Did you See the Sunrise!’). But this blog isn’t concerned with whether or not this is a good episode: my main concern in this blog post is how Magnum deals with the idea of the escaped/unpunished war criminal.

In ‘DHR’, a former SS Captain, Lutze, tours Dachau, the concentration camp he was formerly in charge of during the war. Lutze has escaped any formal punishment, and in the end of the episode, Lutze descends into madness. Twilight Zone takes a very harsh attitude toward those who, like Lutze, look at war through a lens of nostalgia and fail to appreciate the gravity and horror of the Holocaust. A mere 14 years after the war ended, Jewish veteran Serling is understandably resolutely unsympathetic to those who, like Lutze, ‘decided to turn the Earth into a graveyard.’ His message is clear: those who romanticise or fail to recognise the horrors of the Holocaust will be punished – either in this life, or the next.

Magnum, P.I. (1980-1988) approaches the Nazi war criminal 36 years after the end of WWII. In ‘NANA’, the focus on escaped Nazis of WWII can seem somewhat out of character for a programme that focuses so strongly on the Vietnam War. Like both Twilight Zone (TZ) and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (DS9), Magnum is a show very much preoccupied with war – in fact, it would be fair to say that out of these three programmes, Magnum focuses the most consistently on war, repercussions of war, and cultural memory of conflict. TZ and DS9 are science fiction programmes that frequently make direct commentary on war – sometimes in terms of historical wars, and sometimes in terms of fictional wars based upon historical conflict.

Magnum is different: the four principle characters are all veterans of war. Thomas Magnum (Tom Selleck) and his friends Rick Wright (Larry Manetti) and T.C. Calvin (Roger E. Mosley) each served together during the Vietnam War. John Jonathan Higgins (Magnum’s best friend/most hated adversary depending on the day, played by John Hillerman) is retired British Sergeant Major who served in both WWII and Korea, and is, as Elizabeth Hirschman describes, representative of ‘the pomposity, elitism, and stuffiness of the Old Guard (literally and figuratively)’. Moreover, as discussed in the Part 1 blog on TZ, Rod Serling created TZ as a safe place to both discuss and analyse war from his own experiences in the US Army. Magnum, P.I. was similarly informed from first-hand experience, as Selleck served in the National Guard, and Hillerman served in the US Air Force.

War is certainly an ever-present character in Magnum, but not always one that is immediately commented upon. Most episodes are splintered with flashbacks to ‘Nam: some of the flashbacks are addressed within the future, but very often the stories are left hanging as character backstory within the present narrative. Magnum, T.C. and Rick generally do not discuss the Vietnam War, and Higgins is prone to telling war stories: this conforms to the American cultural attitudes of WWII as a ‘romanticised’ war with good stories of heroism and valour in contrast to ‘Nam as a sore wound held within this programme (though there is often an effort to subvert both attitudes frequently within the programme). In fact, Magnum frequently calls Higgins up on his tendency to romanticise his war stories, as seen in this exchange in ‘No More Mr. Nice Guy’ (Season 4, episode 13):

Magnum, P.I., has often been recognised as the first fictional media (film or television programme) that did not demonise veterans and show them as unstable killers, disabled, violent and suffering from debilitating PTSD (see links for examples). In general, I would agree with recognising Magnum as one of, if not the first, television programme that showed Vietnam veterans with sensitivity and respect, and that the programme actively tried to represent Vietnam Vets without demonising them.

In an interview with TV Legends, Creator Donald P. Bellasario comments that the portrayals of Vietnam Vets within the media

was very negative… [as seen in films like In the Valley of Elah, 2007] That everybody comes back so fucked up. Unable to function. Killers. I’m seeing it all over again. […] It leaves an image of people served that I don’t think is accurate. Because Vietnam was exactly the same way. And when I created Magnum, I got thousands of letters from Vietnam veterans thanking me for portraying Vietnam veterans who were something other than killers and drug addicts and crazy and unable to function in society…I never did the image of the guys that they had been in Vietnam and it had been a waltz, that they just loved it. I never did that. It had been a terrible experience. In fact, the key to Magnum was that after all the tours of duty he did, [when the Vietnam War] ended, he just didn’t know what to do. …The key to the whole show: he woke up one day and realized that he was 35 but he’d never been 25. He decided he was gonna be 25 and have a good time. So he was affected by [war]. And so was TC, and so was Rick. But it was quite a departure for television at that time, or for films. And the Village Voice did an article which said they thought it was a seminal moment in television, a changing to acceptance of Vietnam Veterans that had been a long time coming [.] That it was just time to do it.

This positive representation has been recognised by various mainstream press as well as cultural historians like Thomas Doherty, who argues that

Magnum P.I. [sic] celebrated a rakish private investigator who was a veteran of naval intelligence in Vietnam, a man who oozed congeniality and psychic ability and who maintained a bond with his equally capable crew of war buddies – the kind of postwar bond that was common in 1940s cinema. [Through] the great wellspring of traumatic stress and residual shame, the Vietnam War was also the only credible back story for a mature action hero to have acquired skill in weaponry and certification of his courage on the field of battle Periodically tormented by flashbacks and night terrors, he was, by and large, a functioning human being whose Vietnam experience informed his police work and dexterity under fire.

Selleck is a driving force in continued recognition for Vietnam Veterans and the recognition of Magnum as a positive influence on culture and society in terms of Vietnam Veterans, and he serves as a spokesperson for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. In fact, as Selleck explains,

Magnum was a show that was taken very seriously. I’m most proud of the fact that Magnum is in the Smithsonian. They recognized [sic] it as the first show that recognized [sic] Vietnam veterans in a positive light, and that’s why my Detroit hat and my Hawaiian shirt is next to Archie Bunker’s chair.

As a result of this more sensitive approach to recognise Vietnam veterans in a more positive light, the programme inter-spliced flashbacks of ‘Nam into nearly every episode. Generally speaking, each of the four primary characters were shown as highly functional despite any lingering PTSD they may have had, though when the plot called for it, it was certainly Magnum who struggled the most in moving forward. The attitude toward Vietnam Vets and Magnum will certainly be an area of interest for future blogs, but for right now, I’m primarily concerned with the generally positive attitude Magnum held in regards to soldiers and veterans, as it influences how the episode ‘Never Again… Never Again’ approaches war and the idea of war crime.

As argued in Part 1 of this series, Conflict, criminality and atrocities are never easy topics to tackle, especially in television, due to the limited framework of the medium such as time, network restrictions, expectations of the audience, and even budget. TZ, as a half-hour programme, packs a solid and decisive punch in the viewer’s face in ‘DHR’: the cast is minimal, as are the set designs and even dialogue. What sells the punch for ‘DHR’ is the duet between the war criminal, Lutze, and his victim, Alfred Becker.

‘NANA’ seems so concerned with twisting the end to surprise the audience that it fails to deliver a solid punch. In short, this is a programme that concerns itself with action, reaction, and aesthetics. ‘NANA’ is, therefore, primarily focused on these elements and, unlike ‘Duet’ and ‘DHR’, does not necessarily take the time to present a specific point or attitude about how we see war, war criminals and identity. As such, discussing what should happen to those perpetrators of war crimes — in particular, those who have faced no negative consequences for their involvement in war crimes — is a difficult task for any programme, but especially Magnum, P.I.

The plot of ‘NANA’ is simple, if not a bit contrived. Magnum and his friends attempt to help Lena and Saul Greenberg (played by (Hanna Hertelendy and Robert Ellenstein), two Holocaust survivors (pictured below), as they are targeted by a group of Nazi pursuers.

Magnum et. al become suspicious when their very dear friends (that we’ve never met), The Greenbergs, announce they’re going on holiday. When Magnum and Rick go to see the Greenbergs at their shop, they find the shop has closed down.

Worried, they decide to go to the Greenberg’s house to find Saul being taken away in an ambulance with a heart attack.

When the ambulance does not arrive to the hospital, however, they quickly realise, that Saul has been kidnapped. Rick and Magnum work to calm down Lena to figure out where he might have gone.

Magnum asks Lena if she knows who took Saul.

Magnum and Lena meet with Dr Heller, Saul’s doctor who has been treating him for his heart – but Lena vehemently announces that Dr Heller is not Saul’s doctor.

Unlike TZ or DS9, there is no attempt to discuss the horrors of war: imagining an educated viewer who is intimately aware of the Holocaust and Nazis, Magnum instead focuses on Magnum’s efforts to figure out where Saul might be and how to keep Lena safe. Magnum takes Lena to stay on the estate he lives with Higgins on.

Over a cup of tea, Higgins spots Lena’s Holocaust tattoo, apologises for staring, and remarking, ‘it’s been a long time since I’ve seen anything like that.’

Higgins asks which camp she was at, and she replies ‘Jadwiga, Poland’. Fact check: there is no such camp, in fact: it is a fictional camp often used in fictional narratives referencing the Holocaust (such as Leon Uris’s QB VII), and is probably meant to reference Auschwitz, as that is the only camp that tattooed numbers on the prisoners. It is interesting to me that Twilight Zone uses real concentration camps but other shows use fictional ones. I might follow this up at some point in a future post.

Magnum goes to Lena’s house to get her some clothes for her stay at the estate, and Higgins is attacked trying to save Lena from intruders. When Magnum comes home, he finds Higgins unconscious and calls his friend T.C. to take Higgins to the hospital. Lena is no where to be found.

Magnum leaves Higgins at the hospital to try to figure out who might have Lena and Saul. He narrates to the audience:

Magnum contacts Kessler, who asks him to come to his house to discuss the Greenbergs. When Magnum and Rick arrive, however, Kessler is dead.

Magnum contacts Kessler, who asks him to come to his house to discuss the Greenbergs. When Magnum and Rick arrive, however, Kessler is dead.

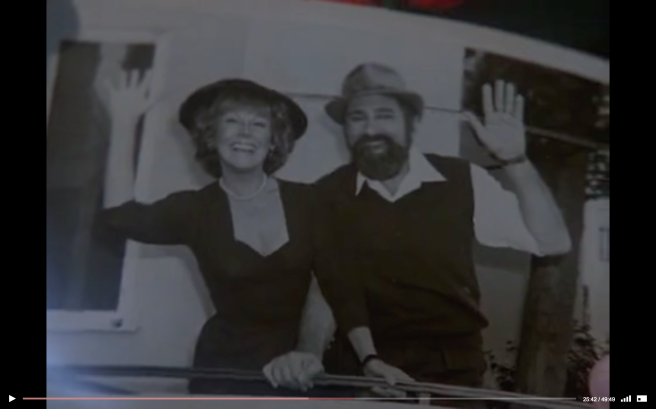

It is at this point Magnum starts putting the pieces together. Kessler does have a number tattooed on his arm – he was in a concentration camp. This makes no sense to Magnum, who wonders if Kessler was a Nazi passing as a Jew. Magnum starts searching Kessler’s desk. He finds a picture of Saul and Lena in Kessler’s files:

Surmising that Lena killed Kessler, Magnum realises that Saul and Lena are probably on Kessler’s boat. When he arrives, he discovers another member of the Israeli Secret Police dead – Lena has slashed the man’s throat with a scalpel. Lena is in the quarters of the boat sobbing over Saul’s dead body – his heart attack, untreated, has killed him.

This exchange is literally the only point in the episode where direct reference is made to the horrors of the concentration camps and the mentality that lead to the camps. In comparison to ‘DHR’, (in which nearly every moment is spent considering the agonies experienced by the prisoners and the sadism of the Nazi officials), the minimal referencing of these in ‘NANA’ has four distinct possibilities for me:

- Firstly, perhaps it is just a poorly written episode that fails to capture the subject it dares to bring up, or suffers from network limitations.

- Secondly, it might be attempting to recognise old adage that the unseen/unspoken can often be more frightening than actually acknowledging it, as it forces the audience to fill in the blanks with their own imagination: whether this episode actually does this adequately is certainly up for debate.

- Thirdly, perhaps, in the dedication to portraying a more favourable attitude toward soldiers, especially Vietnam veterans who are so often represented within popular media as criminals, Magnum leaves the gravity of these crimes almost entirely unspoken as to avoid looking too harsh on the subject of war crime for fear of making inferences to these veterans.

- Finally, perhaps because the programme is an action-adventure — one with a distinct comedic presence — Magnum felt it was too heavy a subject to address on only the seventh episode of the programme (though they certainly dealt with heavier topics within the show).

(Or a combination therein).

Regardless of whether the reasons for this minimalism is addressed here, I find it interesting that out of the three shows discussed in this series, the one that engages most consistently with war in this series is the one show that hides away from it so much.

It is assumed that Magnum takes Lena into custody (though this is not shown to the audience) to pay for her crimes, but no resolution is even hinted at. An interesting take here for Magnum is in having Lena — an elderly woman — the villain of the episode, as this does seem an unusual approach. Magnum certainly tends to have it’s fair share of femme fatales — usually played by actresses like Sharon Stone. In any case, ‘NANA’ seems more preoccupied with presenting an altogether serviceable but hardly original twist ending reveals that Lena and Saul are not, in fact, Jewish survivors being hunted by Nazis, but in fact Nazis being hunted by the Israeli Secret Police.

One thing I do want to unpick a bit here is Lena’s repeated attempts at justification, ‘it was war!’, as the denouement of the episode addresses this.

Magnum drives Higgins home from the hospital, and as they walk along the beach, they have this very brief exchange:

Magnum drives Higgins home from the hospital, and as they walk along the beach, they have this very brief exchange:

In some ways, this conversation seems to belong to a different episode — one that might have done more than barely flash through any question of the realities of the camps, nor of the excuses like ‘it was war’ from those who committed these atrocities. We never know how involved Saul and Lena were in the Holocaust – we do know that Lena has killed two people in this episode, however. Whether they were ‘little fish’ or not, the episode seems completely non-plussed in answering this question. Nevertheless, for all the minimalism and even avoidance of the very topic ‘Never Again… Never Again’ brings to the table, this idea of the ‘little fish’ and the insistence that there were no ‘little fish’ is the most straightforward.

Like ‘Deaths-Head Revisted’, Magnum, P.I. declares here that whether they were ‘little fish’ or running the camps themselves, those who might try to justify the Holocaust by arguing that they did what they did because ‘it was war’ might meet the same end as Twilight Zone‘s Lutze. I argued in Part 1 of this series that Twilight Zone takes the harshest view toward war criminals for a variety of reasons. The time between the Second World War and this episode of Magnum, P.I. is 36 years – the same number, funnily enough, between today and this episode of Magnum. This distance is certain to change perceptions one way or another. In Serling’s ‘Deaths-Head Revisited’, wounds still sore and open from war, the attitude toward people like Lutze — and, indeed, to people like Lena and Saul. Although Magnum, P.I. approaches the idea of the escaped war criminal differently than Twilight Zone, ultimately each refuse to accept any idea of a ‘little fish’, arguing that everyone involved must be held accountable for the crimes and atrocities they allowed to happen.

In the final blog in this series, I explore the episode ‘Duet’ in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. In many ways, ‘Duet’ has far more in common with ‘Deaths-Head Revisted’, depite the amount of time between the two. Continuing this idea of what Higgins calls the ‘little fish’, ‘Duet’ explores fictional war criminals in a futuristic setting. As I will argue, however, the setting and details may change, but the question of what to do with someone who has taken part in an atrocity like the Holocaust after the war has ended still lingers.

Dr. Harmon: Maybe it’s never over. Maybe we always carry the war around inside of us. Like a time bomb, ticking away, waiting to go off. – Magnum, P.I., Heal Thyself [3.12]